Authored by Christian Ostermann, Ph.D.

For nearly half a century, between 1945 and 1989/91, the Cold War shaped how people in the United States lived their lives and thought about politics and the world in ways that are easily forgotten yet remain powerfully relevant today. The Cold War was so all-encompassing in its impact because it was both a military confrontation that had the potential destroy much of human civilization, and — somewhat paradoxically — also a confrontation between two competing universalist conceptions of how to build modern industrial civilizations. It was, in other words, a militarized clash of two systems, the Western model of pluralist democracy and market economy on the one hand and the Soviet model of communist dictatorships and state socialism on the other. For American leaders and citizens, what was at stake in fighting the Cold War was nothing less than the survival of the “American way of life.”

Authored by Christian Ostermann, Ph.D.

For nearly half a century, between 1945 and 1989/91, the Cold War shaped how people in the United States lived their lives and thought about politics and the world in ways that are easily forgotten yet remain powerfully relevant today. The Cold War was so all-encompassing in its impact because it was both a military confrontation that had the potential destroy much of human civilization, and — somewhat paradoxically — also a confrontation between two competing universalist conceptions of how to build modern industrial civilizations. It was, in other words, a militarized clash of two systems, the Western model of pluralist democracy and market economy on the one hand and the Soviet model of communist dictatorships and state socialism on the other. For American leaders and citizens, what was at stake in fighting the Cold War was nothing less than the survival of the “American way of life.”

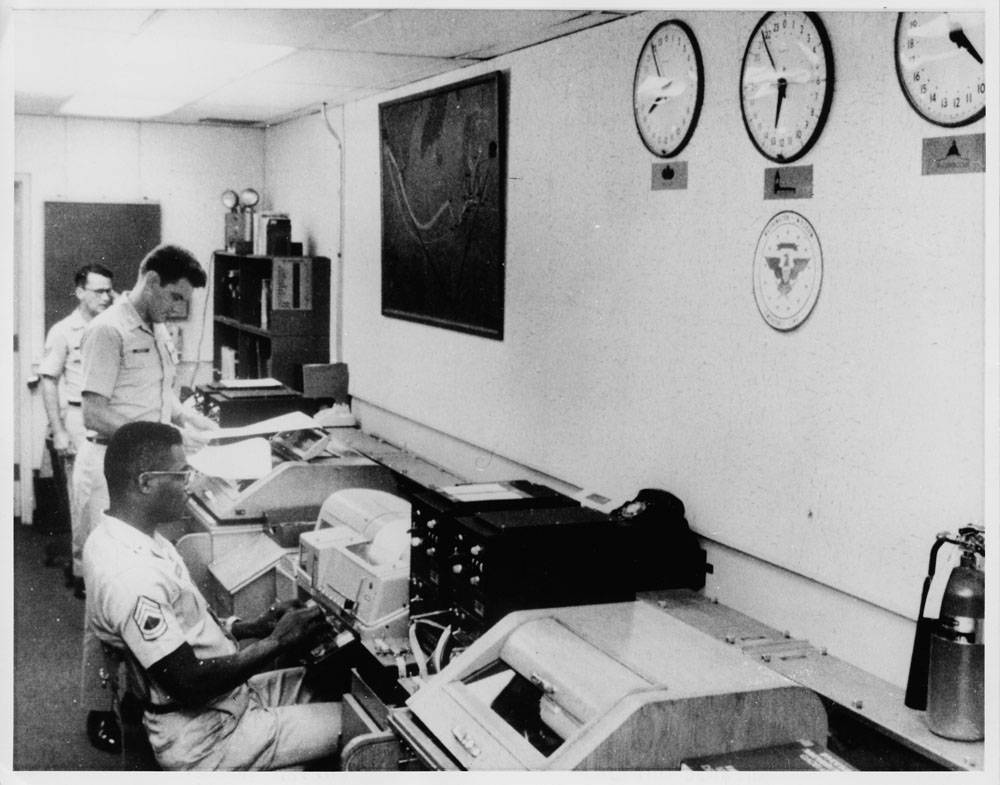

Fighting the Cold War required new national security instruments beyond the military: the 1947 National Security Act created a new National Security Council that was to coordinate the Cold War effort across the federal government. Building on the wartime beginnings of the Office of Strategic Services, the newly established Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) sought to centralize and coordinate the rapidly expanding intelligence gathering aimed at the Soviet-Communist adversary. Out of the public eye, an expanding U.S. intelligence community employed human, signals, and imagery intelligence to understand Soviet capabilities and intentions. Shrouded in secrecy to this day, these “national technical means” would at later stages of the Cold War become critical to monitoring Soviet forces and verifying arms control agreements. U.S. Covert actions attempted to manipulate the course of the Cold War by methods ranging from bribing opinion-makers to paramilitary operations.

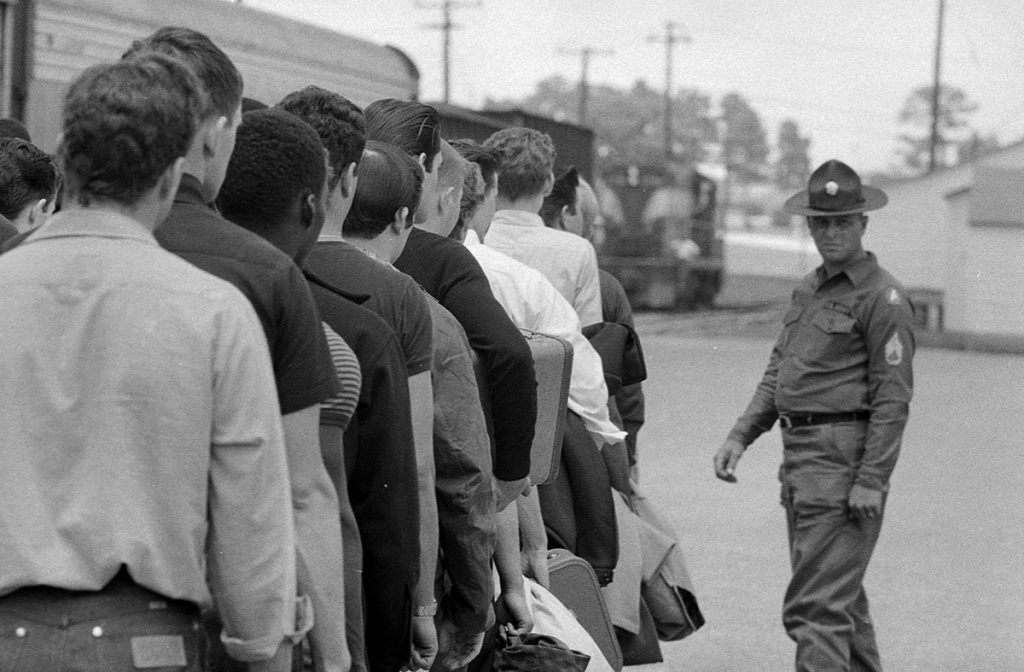

As thousands of U.S. diplomats, intelligence operatives, Marshall Plan officials and advisers headed to Europe, fears over Soviet-communist inroads also surfaced in Asia, especially following the victory of the communists in the Chinese civil war in 1949. Triggered by the unexpected, Soviet-sanctioned North Korean invasion of the U.S.-backed Republic of Korea in June 1950, the Korean War (1950-1953) supercharged these anxieties. Congress approved the tripling of the U.S. defense budget. Fears of future Soviet attacks caused the full-scale militarization of American containment strategy. At home, myriad civil defense programs, including the Federal Civil Defense Administration, sought to prepare American for a nuclear war through education, emergency drills, a system of fallout shelters and the Emergency Broadcast System.

Fighting the Cold War required new national security instruments beyond the military: the 1947 National Security Act created a new National Security Council that was to coordinate the Cold War effort across the federal government. Building on the wartime beginnings of the Office of Strategic Services, the newly established Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) sought to centralize and coordinate the rapidly expanding intelligence gathering aimed at the Soviet-Communist adversary. Out of the public eye, an expanding U.S. intelligence community employed human, signals, and imagery intelligence to understand Soviet capabilities and intentions. Shrouded in secrecy to this day, these “national technical means” would at later stages of the Cold War become critical to monitoring Soviet forces and verifying arms control agreements. U.S. Covert actions attempted to manipulate the course of the Cold War by methods ranging from bribing opinion-makers to paramilitary operations.

As thousands of U.S. diplomats, intelligence operatives, Marshall Plan officials and advisers headed to Europe, fears over Soviet-communist inroads also surfaced in Asia, especially following the victory of the communists in the Chinese civil war in 1949. Triggered by the unexpected, Soviet-sanctioned North Korean invasion of the U.S.-backed Republic of Korea in June 1950, the Korean War (1950-1953) supercharged these anxieties. Congress approved the tripling of the U.S. defense budget. Fears of future Soviet attacks caused the full-scale militarization of American containment strategy. At home, myriad civil defense programs, including the Federal Civil Defense Administration, sought to prepare American for a nuclear war through education, emergency drills, a system of fallout shelters and the Emergency Broadcast System.

Scientists, too, were mobilized into service for the Cold War. At top universities, weapons laboratories and in the defense industry, scientists and engineers, frequently under contract by the U.S. government, developed new weapons systems, spurring, with massive support by tax-payers’ dollars, technological innovations that bolstered military capabilities, space exploration and industrial production. Stepped up efforts led to the successful test of a hydrogen bomb in 1952 that was a thousand times more powerful than the atomic bombs that had devastated Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Over the following decade, the United States built up of a large U.S. nuclear stockpile and acquired bombers, submarines, missiles and guns that could deliver the weapons to target, driven in part by exaggerated fears that the country had been outpaced by the USSR. Nuclear threats, the ever-present risk of accidental nuclear war through miscalculations, and fears of a preemptive strike by the other made these years among the most tense of the Cold War era. Provoked by Soviet leader Nikita S. Khrushchev’s decision to send nuclear missiles to Cuba to defend the Fidel Castro’s revolution, the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis brought the world perilously close to a nuclear conflagration. By the mid-1960s the United States found itself locked in a strategic stalemate with the Soviet Union: either could deter a potential attack inflicting massive death and destruction on the other.

Scientists, too, were mobilized into service for the Cold War. At top universities, weapons laboratories and in the defense industry, scientists and engineers, frequently under contract by the U.S. government, developed new weapons systems, spurring, with massive support by tax-payers’ dollars, technological innovations that bolstered military capabilities, space exploration and industrial production. Stepped up efforts led to the successful test of a hydrogen bomb in 1952 that was a thousand times more powerful than the atomic bombs that had devastated Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Over the following decade, the United States built up of a large U.S. nuclear stockpile and acquired bombers, submarines, missiles and guns that could deliver the weapons to target, driven in part by exaggerated fears that the country had been outpaced by the USSR. Nuclear threats, the ever-present risk of accidental nuclear war through miscalculations, and fears of a preemptive strike by the other made these years among the most tense of the Cold War era. Provoked by Soviet leader Nikita S. Khrushchev’s decision to send nuclear missiles to Cuba to defend the Fidel Castro’s revolution, the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis brought the world perilously close to a nuclear conflagration. By the mid-1960s the United States found itself locked in a strategic stalemate with the Soviet Union: either could deter a potential attack inflicting massive death and destruction on the other.

The Cuban Missile Crisis gave renewed impetus to the efforts by diplomats and citizens to constrain the arms race and reduce the risk of general war. As nuclear conflict was increasingly understood by both sides as unacceptable given its devastating human and ecological costs, the Cold War competition flourished in other fields. Successive U.S. administrations deployed a broad arsenal of political, propaganda, economic, and cultural instruments to win the “hearts and minds” behind the Iron Curtain and in the Third World. In response to early Soviet propaganda and psychological warfare, the United States launched its own information and student exchange programs, such as the Fulbright scholarships. The Smith-Mundt Act of 1948 authorized peace time propaganda overseas. Complementing overt U.S. government media as the Voice of America, the CIA mounted its own covert campaign through Radio Free Europe and later Radio Liberty, employing exiles and émigrés from the East to broadcast news and western views into the Soviet bloc. In 1950, Truman sought to enlist journalists in a “Campaign of Truth” to win the cold war. Financed in part by U.S. intelligence agencies, a growing network of private anti-communist organizations sought to place Communist regimes on the defensive. In 1953, President Dwight D. Eisenhower established the United States Information Agency (USIA) to conduct all U.S. information work around the world. American efforts included massive programs to translate and publish anti-communist books and journals for dissemination in the Warsaw Pact States and the developing world. The State Department and USIA, in what was commonly referred to “public diplomacy” after 1965, sponsored concert tours, created documentaries, secretly subsidized international newsreels and guided script decisions at major Hollywood studios to shape output with Cold War concerns in mind. Efforts to broaden the flow of Western ideas into the Soviet bloc expanded after the 1975 Helsinki Accords legitimized greater East-West contacts. International exchanges increased Soviet awareness of the life in the West, put realities in the East in a sharper relief and encouraged dissident impulses in the East.

The Cuban Missile Crisis gave renewed impetus to the efforts by diplomats and citizens to constrain the arms race and reduce the risk of general war. As nuclear conflict was increasingly understood by both sides as unacceptable given its devastating human and ecological costs, the Cold War competition flourished in other fields. Successive U.S. administrations deployed a broad arsenal of political, propaganda, economic, and cultural instruments to win the “hearts and minds” behind the Iron Curtain and in the Third World. In response to early Soviet propaganda and psychological warfare, the United States launched its own information and student exchange programs, such as the Fulbright scholarships. The Smith-Mundt Act of 1948 authorized peace time propaganda overseas. Complementing overt U.S. government media as the Voice of America, the CIA mounted its own covert campaign through Radio Free Europe and later Radio Liberty, employing exiles and émigrés from the East to broadcast news and western views into the Soviet bloc. In 1950, Truman sought to enlist journalists in a “Campaign of Truth” to win the cold war. Financed in part by U.S. intelligence agencies, a growing network of private anti-communist organizations sought to place Communist regimes on the defensive. In 1953, President Dwight D. Eisenhower established the United States Information Agency (USIA) to conduct all U.S. information work around the world. American efforts included massive programs to translate and publish anti-communist books and journals for dissemination in the Warsaw Pact States and the developing world. The State Department and USIA, in what was commonly referred to “public diplomacy” after 1965, sponsored concert tours, created documentaries, secretly subsidized international newsreels and guided script decisions at major Hollywood studios to shape output with Cold War concerns in mind. Efforts to broaden the flow of Western ideas into the Soviet bloc expanded after the 1975 Helsinki Accords legitimized greater East-West contacts. International exchanges increased Soviet awareness of the life in the West, put realities in the East in a sharper relief and encouraged dissident impulses in the East.  While the confrontation in Europe (centered on the future of Germany) stabilized into an uneasy standoff after the 1958-61 Berlin Crisis (and the building of the Berlin Wall), the global South became the main – and often violent — battleground of the superpower competition. Khrushchev had boldly vowed Soviet support for wars of liberation across the developing world. Many in the United States, led by President John F. Kennedy, felt that the global balance of power was at stake if the new post-colonial states gravitated to the Soviet orbit. With economic aid considered the most effective tool to win favor with the developing world, thousands of U.S. economic, political and military advisers became Cold War combatants. The Kennedy administration’s boldest Third World program was the “Alliance for Progress” which sought to use economic largesse to spur modernization, alleviate poverty and address educational and health needs in Latin America. Similarly, the Peace Corps that sent thousands of young idealistic volunteers to some of the world’s least developed countries sprang from a wider strategic vision that emphasized the need to wage the Cold War in the Third World with greater effectiveness. That effort also included devising new ways to deal with revolutionary insurgencies, including the creation of “Special Forces” that sought to apply new counterinsurgency techniques to combat guerilla movements. In what became the United States’ longest, costliest and most controversial intervention in the Global South, the administration of President Lyndon B. Johnson resorted in 1965 to a full-scale U.S. military intervention and an ambitious if ultimately failed nation-building project in South Vietnam, hoping to prevent the Viet Cong (Vietnamese communists) from taking over the country.

President Richard Nixon’s détente policy sought to extricate the United States from Indochina without appearing to have been forced out, to stabilize the Cold War by engaging the USSR in arms control and economic negotiations, and, through his spectacular diplomatic opening to the People’s Republic of China, to regain the advantage in the Cold War. The Nixon strategy of establishing a “linkage” between inducements and constraints led to the U.S. withdrawal from Vietnam and a series of high-level summits and strategic arms control agreements. Yet Soviet interventions in Angola, Ethiopia, and Afghanistan, crises in the Middle East, and U.S. domestic constraints (anti-war protests, Watergate) caused a collapse of the superpower détente by the end of the 1970s. Superpower relations turned frigid in the “second Cold War” of the 1980s; by the early 1980s the nuclear danger was greater than at any point since the Cuban Missile Crisis.

While the confrontation in Europe (centered on the future of Germany) stabilized into an uneasy standoff after the 1958-61 Berlin Crisis (and the building of the Berlin Wall), the global South became the main – and often violent — battleground of the superpower competition. Khrushchev had boldly vowed Soviet support for wars of liberation across the developing world. Many in the United States, led by President John F. Kennedy, felt that the global balance of power was at stake if the new post-colonial states gravitated to the Soviet orbit. With economic aid considered the most effective tool to win favor with the developing world, thousands of U.S. economic, political and military advisers became Cold War combatants. The Kennedy administration’s boldest Third World program was the “Alliance for Progress” which sought to use economic largesse to spur modernization, alleviate poverty and address educational and health needs in Latin America. Similarly, the Peace Corps that sent thousands of young idealistic volunteers to some of the world’s least developed countries sprang from a wider strategic vision that emphasized the need to wage the Cold War in the Third World with greater effectiveness. That effort also included devising new ways to deal with revolutionary insurgencies, including the creation of “Special Forces” that sought to apply new counterinsurgency techniques to combat guerilla movements. In what became the United States’ longest, costliest and most controversial intervention in the Global South, the administration of President Lyndon B. Johnson resorted in 1965 to a full-scale U.S. military intervention and an ambitious if ultimately failed nation-building project in South Vietnam, hoping to prevent the Viet Cong (Vietnamese communists) from taking over the country.

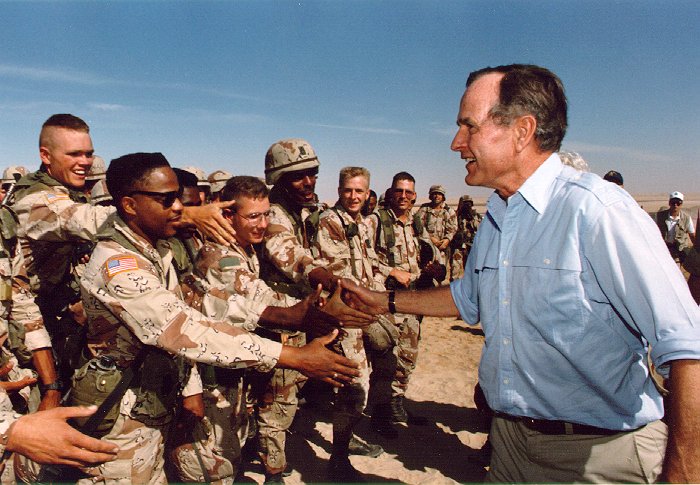

President Richard Nixon’s détente policy sought to extricate the United States from Indochina without appearing to have been forced out, to stabilize the Cold War by engaging the USSR in arms control and economic negotiations, and, through his spectacular diplomatic opening to the People’s Republic of China, to regain the advantage in the Cold War. The Nixon strategy of establishing a “linkage” between inducements and constraints led to the U.S. withdrawal from Vietnam and a series of high-level summits and strategic arms control agreements. Yet Soviet interventions in Angola, Ethiopia, and Afghanistan, crises in the Middle East, and U.S. domestic constraints (anti-war protests, Watergate) caused a collapse of the superpower détente by the end of the 1970s. Superpower relations turned frigid in the “second Cold War” of the 1980s; by the early 1980s the nuclear danger was greater than at any point since the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Yet within a few years the Cold War came to a peaceful end. Soviet “imperial overstretch” in the Third World compounded a “crisis of legitimacy” that had been rotting the Soviet system at its core (1953 East German Uprising, 1956 Hungarian revolution, 1968 Prague Spring, 1980/81 Polish Martial Law). The growing economic, technological and military disparity between vibrant democratic capitalism in the West and faltering state socialism in the East finally produced the “basic change” in Soviet foreign policy that the West had sought all along: under Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev the USSR abandoned expansionist ambitions and embarked on domestic reforms. President Ronald Reagan found in Gorbachev a negotiating partner who came to share his vision of ending the Cold War. No longer propped up by Soviet support, communist regimes in Eastern Europe collapsed in the face of popular protests in 1989, leading to the fall of the iconic Berlin Wall in November of that year, and two years later, to the dissolution of the USSR. The West had emerged victorious from the Cold War.

Yet within a few years the Cold War came to a peaceful end. Soviet “imperial overstretch” in the Third World compounded a “crisis of legitimacy” that had been rotting the Soviet system at its core (1953 East German Uprising, 1956 Hungarian revolution, 1968 Prague Spring, 1980/81 Polish Martial Law). The growing economic, technological and military disparity between vibrant democratic capitalism in the West and faltering state socialism in the East finally produced the “basic change” in Soviet foreign policy that the West had sought all along: under Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev the USSR abandoned expansionist ambitions and embarked on domestic reforms. President Ronald Reagan found in Gorbachev a negotiating partner who came to share his vision of ending the Cold War. No longer propped up by Soviet support, communist regimes in Eastern Europe collapsed in the face of popular protests in 1989, leading to the fall of the iconic Berlin Wall in November of that year, and two years later, to the dissolution of the USSR. The West had emerged victorious from the Cold War.

Three decades after the end of the conflict, the world looks much different: the disintegration of the USSR and Western victory in the Cold War produced for a few years a “unipolar moment” (with the United States as the sole superpower) that has since given way to a multipolar system that for centuries has been the normal state of international politics. Yet the Cold War’s legacies are still with us today: the Western victory brought democratic governance and market economies to large areas in the world once under communist dictatorships. The acute threat of a nuclear Armageddon has lessened. The ideological confrontation between capitalism and communism has faded. Yet the Cold War’s last impact is also visible in regimes from China to North Korea that still claim authoritarian forms of legitimacy that originate in the Cold War. In the Cold War’s battlegrounds in the global South, from East Africa to Afghanistan, humanity still deals with the environmental threats, social and racial divides, and ethnic conflicts caused, stimulated or perpetuated by the Cold War. The Cold War’s scars continue to pose challenges to the world in the 21rst century.

Three decades after the end of the conflict, the world looks much different: the disintegration of the USSR and Western victory in the Cold War produced for a few years a “unipolar moment” (with the United States as the sole superpower) that has since given way to a multipolar system that for centuries has been the normal state of international politics. Yet the Cold War’s legacies are still with us today: the Western victory brought democratic governance and market economies to large areas in the world once under communist dictatorships. The acute threat of a nuclear Armageddon has lessened. The ideological confrontation between capitalism and communism has faded. Yet the Cold War’s last impact is also visible in regimes from China to North Korea that still claim authoritarian forms of legitimacy that originate in the Cold War. In the Cold War’s battlegrounds in the global South, from East Africa to Afghanistan, humanity still deals with the environmental threats, social and racial divides, and ethnic conflicts caused, stimulated or perpetuated by the Cold War. The Cold War’s scars continue to pose challenges to the world in the 21rst century.© Copyright 2022. All rights reserved. | Terms of Use | Privacy Policy | Vendor Code of Conduct

Check back here for a response within 24 hours.

These are cookies that are required for the operation of our Website and are necessary to enable the basic features of the site to function and to do so securely and optimally. For example, these cookies themselves allow you to select your cookie preferences.

These cookies are used to track point of entry to point of registration for those users participating in our affiliate signup programs, and to track and measure the success of a particular marketing campaign. Some of these analytical cookies are processed by third parties, including Bounteous Inc. which is an online analytics company that partners with Google Inc to provide analytical data. This data also helps us understand how our users are interacting with the Website.

These cookies allow us to recognize and count the number of visitors, and to see how visitors move around our website when they are using it, so we can see how our services are performing. These cookies may track things such as how long you spend on the Website or pages you visit and are used for the legitimate purpose of improving the way our Website works by, for example, ensuring that you find what you are looking for easily.

These cookies are used to track point of entry to point of registration for those users participating in our affiliate signup programs, and to track and measure the success of a particular marketing campaign. Some of these analytical cookies are processed by third parties, including Bounteous Inc. which is an online analytics company that partners with Google Inc to provide analytical data. This data also helps us understand how our users are interacting with the Website.

These cookies record your visit to our Website, the pages you have visited and the links you have followed to make our Website more relevant to your interests and provide you with interest-based advertising. We may also share this information with Bounteous for these purposes. Data collected may includes user journey, gender, geolocation, affinity interests.

Other uncategorized cookies are those that are being analyzed and have not been classified into a category as yet.